Magnum photographer Emin Ozmen recalls the day in 1993 when radical Islamists opened fire on the Madimak Hotel in his hometown of Sivas, Turkey, killing 37 people. Intellectuals and artists gathered there for a celebration in honor of the 16th-century Alevi poet.

Many of the dead were Alevis, members of a Muslim sect that is a minority in Turkey. During the 1970s, right-wing Sunni groups often fought Alevi left-wing groups in the streets. Ultimately the violence subsided, but tensions remained – the Panic in Madimak, when Ozmen was 8 years old, was the result. This prompted Ozmen to become a witness.

A mourning crowd at the Kocaitepe Mosque in Ankara, a day after a failed coup attempt by the Turkish military in July 2016 that killed at least 265 people, including soldiers, police and civilians

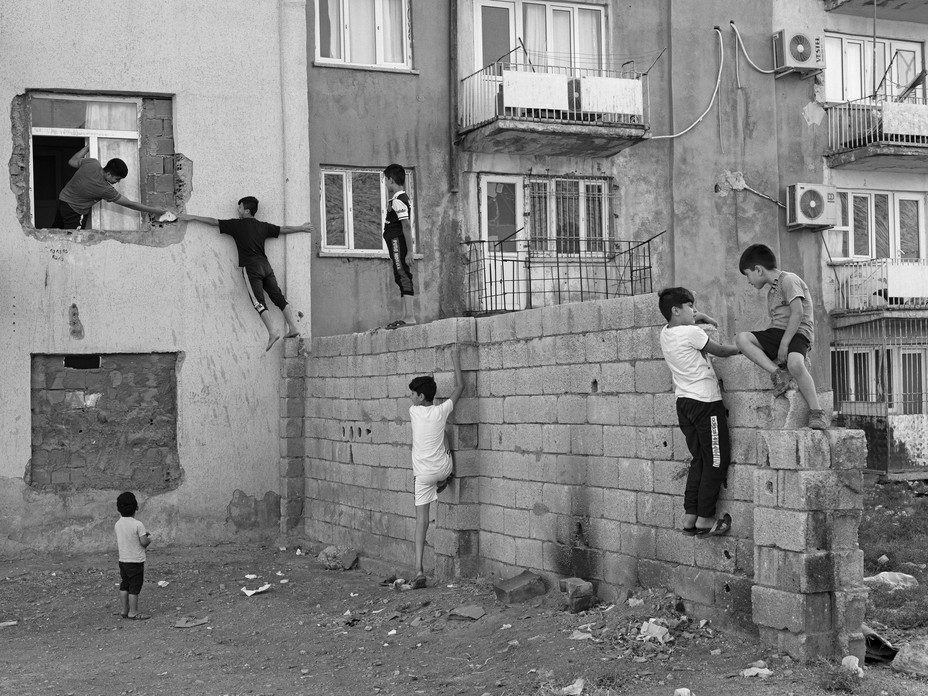

A mourning crowd at the Kocaitepe Mosque in Ankara, a day after a failed coup attempt by the Turkish military in July 2016 that killed at least 265 people, including soldiers, police and civilians  Syrian children play in the Istasian neighborhood of Mardin on October 2, 2020.

Syrian children play in the Istasian neighborhood of Mardin on October 2, 2020.  Demonstrators support Boğaziçi students, who were arrested in March 2021 for showing a rainbow flag, at another protest in Istanbul.

Demonstrators support Boğaziçi students, who were arrested in March 2021 for showing a rainbow flag, at another protest in Istanbul.

On Sunday, May 14, Kemal Kilikdaroglu, Turkey’s first Alevi candidate for the presidency, faced off against Turkey’s longtime dictator, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, a Sunni Muslim who had been in office for five years before Ozmen became a working photojournalist in 2003. came to power earlier. Over the course of Ozmen’s career, he has witnessed and documented how Erdogan transformed Turkey from an aspiring democracy to a polarized autocracy with a failing economy.

Ayşegül Sert: Türkiye’s trust in the government has turned to dust

Turks who have suffered from repression, violence and hunger over the past 20 years believed that Kılıçdaroğlu might have a chance to win this week, despite his vocal opposition from Turkey’s right-wing populace. Despise because he is an Alevi moderate and because he is not Recep Tayyip Erdogan. But none of the candidates got the required 50 percent votes. The election will end on May 28, and Erdogan still has a chance – many Turks see it as a foregone conclusion – to prevail as president for the next five years.

“An entire generation and I were the only ones to know this shade,” Ozman writes in his beautiful new book, ole, “To try to be myself in spite of this shadow, to grow up in spite of this shadow. That shadow is still there twenty years later.

Left: In 2020, a fire broke out near a gas station in Hasankeyf. Correct: The dead bodies of 12 people have been kept in Sirnak’s slaughter house.

Left: In 2020, a fire broke out near a gas station in Hasankeyf. Correct: The dead bodies of 12 people have been kept in Sirnak’s slaughter house.  In September 2014 Turkish riot police use tear gas as Syrian Kurds illegally cross the Turkish-Syrian border in Suruk.

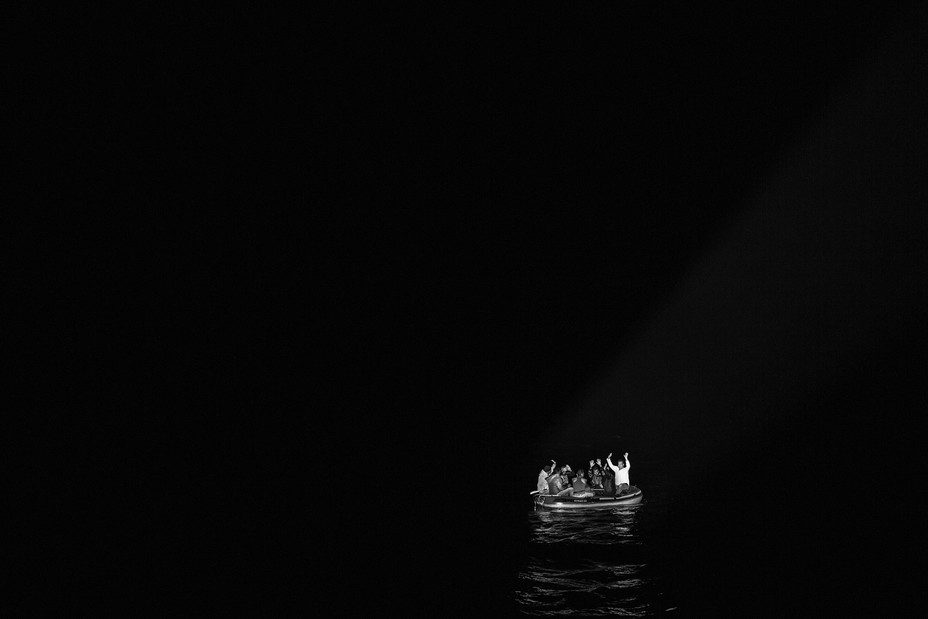

In September 2014 Turkish riot police use tear gas as Syrian Kurds illegally cross the Turkish-Syrian border in Suruk.  A boat full of migrants is illuminated by the flashlights of Turkish coast guards who came to rescue migrants near the Greek-Turkish border. The small boat’s engine failed and seven refugees from Syria, Pakistan and Afghanistan were stranded in the middle of the sea near Bodrum in 2015.

A boat full of migrants is illuminated by the flashlights of Turkish coast guards who came to rescue migrants near the Greek-Turkish border. The small boat’s engine failed and seven refugees from Syria, Pakistan and Afghanistan were stranded in the middle of the sea near Bodrum in 2015.

Ozmen tries to capture in his photographs the horror that his generation and his people have suffered, especially in the last 10 years. As he writes, many Turks have been silenced under Erdogan, and his pictures, even those of active violence, have an eerie mortification to them, like having the volume turned down on a TV. (His work recalls Gilles Pérez’s influential telex iran.) Özmen uses this quality to describe it as a feeling of “powerlessness in the face of so much injustice and violence”.

The events for which (ole can mean “event” or “incident” in Turkish) are famous: the Gezi Park protests of 2013, in which thousands of people protested the construction of a mall on one of Istanbul’s last stretches of green space. rebelled; the 2015 war between the Turkish state and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in the southeast; an attempted military coup against Erdogan in 2016; The ongoing Syrian-refugee crisis.

Most of the photographs are black-and-white and without captions, choices that foster a strange effect of universality – documenting tragedies such as those Turkish people collectively experienced, even if they themselves never took to the streets, or fled the bomb, or attempted to cross the Greek border illegally. The events are what the Turks carry within themselves; They are what their country has become. Ozmen refers to his mind as “the victim of a violent wind”.

Left: Smoke and tear gas fill the sky as Turkish police and protesters clash near Taksim Square in Istanbul on the first day of the Gezi Park protests in June 2013. Correct: The minaret of a sunken mosque emerges from the reservoir of the Biresik Dam in Gaziantep, 2019.

Left: Smoke and tear gas fill the sky as Turkish police and protesters clash near Taksim Square in Istanbul on the first day of the Gezi Park protests in June 2013. Correct: The minaret of a sunken mosque emerges from the reservoir of the Biresik Dam in Gaziantep, 2019.  People watch from a building as protesters clash with Turkish police during the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in June 2013. Civil unrest began in May 2013, when a protester protesting an urban-development plan was violently cleared from the park.

People watch from a building as protesters clash with Turkish police during the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in June 2013. Civil unrest began in May 2013, when a protester protesting an urban-development plan was violently cleared from the park.  A woman lies on the ground in shock after police used tear gas to disperse a crowd at Taksim Square on the first day of the Gezi Park protest in Istanbul in May 2013.

A woman lies on the ground in shock after police used tear gas to disperse a crowd at Taksim Square on the first day of the Gezi Park protest in Istanbul in May 2013.  People gather in Istanbul to show solidarity with Palestinians following Israel’s attack on Palestinian civilians at the Gaza border in May 2018.

People gather in Istanbul to show solidarity with Palestinians following Israel’s attack on Palestinian civilians at the Gaza border in May 2018.

During the decade that Ozmen recorded, Turkey endured several natural disasters: earthquakes in Van, Elazig and Düzce, as well as wildfires in the Aegean region. The government’s response to these events surprisingly failed many Turks. He was the harbinger of the future of the country.

In February, two devastating earthquakes struck southern Turkey in 24 hours, killing at least 50,000 and hundreds of thousands more, while leaving millions homeless. Much has been written about why the earthquake was so deadly. Erdogan had built his authoritarian regime on a corrupt manufacturing economy and so centralized the state around himself that many of its institutions failed to respond to the disaster. In many ways, the weeks following the earthquake felt like the culmination of the psychological experience of the Turkish people over the past 20 years.

Read: Is this the end for Erdogan?

The Turks were not only grieving or panicked in February. Many knew that the dystopian future of the 21st century that haunts our collective dreams, whether because of climate change or war or totalitarianism, had come for them. Thousands of people, rich and poor, lay crushed under their possessions, and as day turned to night, in rain and snow, bodies lay in the street with no one to bury them; Men, women and children were screaming from the rubble and there was no one to save them.

The survivors were forced to look at this new world: their families gone, their homes gone, food and water gone, roads gone, airports and seaports gone, police gone, fire departments gone. They now lived in a wasteland, as we often say that only nature is powerful enough to create. But only humans could have built such a grandly rigged apocalypse, and in 2023, the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Turkey, this act of creation was an act of one.

Turks always remind me that their country has been around for a long time. The Erdoğan era has only lasted 20 years, and even this powerful man cannot crush the history of the Turkish people – the enduring, democratic desire to live and love that Ozmen so heartily portrays in his photographs .

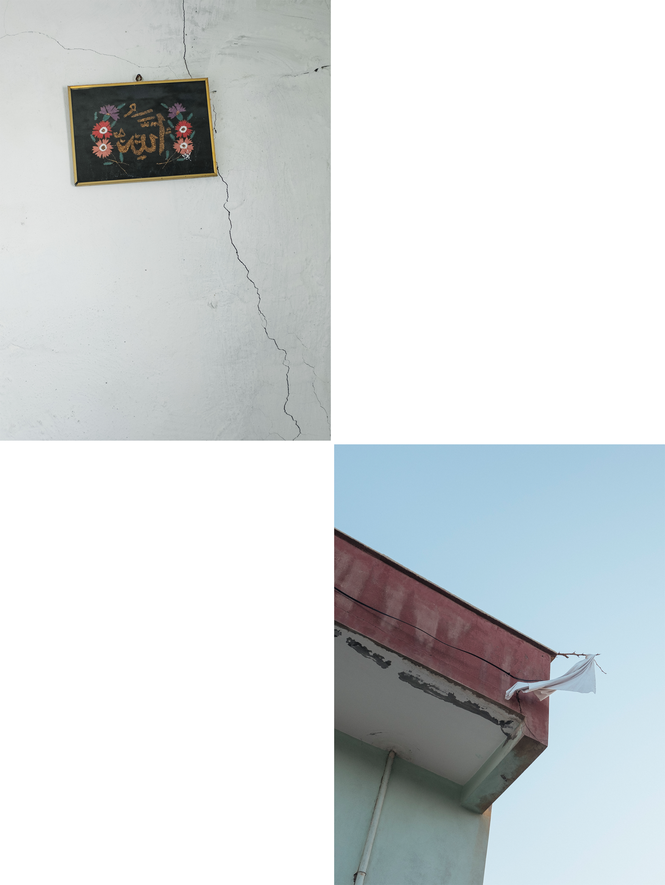

Left: A religious frame with the inscription “God” remains on a broken wall of a house in Hasankeyf, an abandoned historical town in Batman, which was encircled by the Illisu Dam project a few months later in 2020. Correct: In January 2016, citizens in Nusaybin hung a white flag on their houses to show that they were unarmed. Since October 2, 2015, Turkish authorities have imposed seven very strict curfews in this Kurdish city in southeastern Turkey.

Left: A religious frame with the inscription “God” remains on a broken wall of a house in Hasankeyf, an abandoned historical town in Batman, which was encircled by the Illisu Dam project a few months later in 2020. Correct: In January 2016, citizens in Nusaybin hung a white flag on their houses to show that they were unarmed. Since October 2, 2015, Turkish authorities have imposed seven very strict curfews in this Kurdish city in southeastern Turkey.  People remove the bodies of their loved ones and relatives from the village cemetery after the water level in the Ilisu Dam Reservoir lake rose due to a government hydroelectric project in Sirnak in September 2019.

People remove the bodies of their loved ones and relatives from the village cemetery after the water level in the Ilisu Dam Reservoir lake rose due to a government hydroelectric project in Sirnak in September 2019.  People in shock flee their homes during fighting between Turkish forces and Kurdish PYD rebels in 2019, when Turkey launched its military operation in northern Syria.

People in shock flee their homes during fighting between Turkish forces and Kurdish PYD rebels in 2019, when Turkey launched its military operation in northern Syria.  In August 2021, a fire broke out in Dalaman, a village near the airport. In July and August 2021, 299 wildfires ravaged Turkey’s Mediterranean region in the worst wildfire season in the country’s history.

In August 2021, a fire broke out in Dalaman, a village near the airport. In July and August 2021, 299 wildfires ravaged Turkey’s Mediterranean region in the worst wildfire season in the country’s history.

A month after the earthquake, I was having dinner on the terrace of my hotel in Iskenderun, where a group of men and women were sitting at nearby tables, drinking and smoking. A car stopped and a woman got out screaming, and a blonde woman from across the table ran to help her sit up.

“How could I not know they were dead!” she cried. “I just saw it on Facebook… how did I not know!”

He consoled her. She kept on crying. He tried strong words.

“Sister, calm down,” said a man. “We have to be strong. Look, I’ve buried 40 friends.”

They were sipping from a bottle of wine under the table, ordering more. The woman was still crying. The blonde woman spoke to him again in a clear voice.

He said, “Sister, God is testing us.” “see her.” She nodded to the other woman across the table, who bowed her head. “His friend is in the hospital. When they found their children in the rubble, they hugged.”