whyYou, me and all of us know: whether you are aware of it or not, you are in a relationship with a monster.

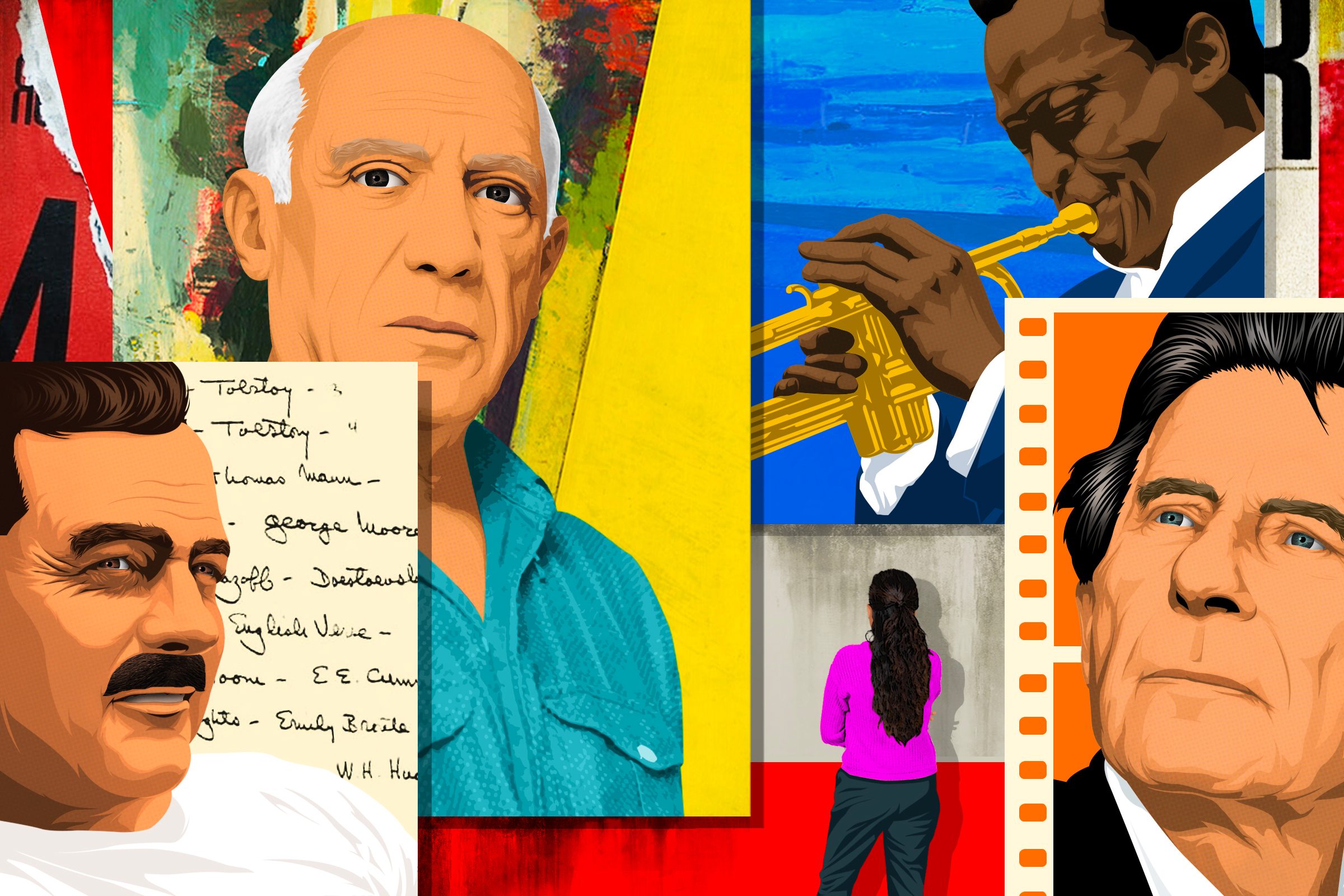

Surely there is some artist whose behavior, known to you or otherwise, is outrageous, reprehensible, possibly deserving of life imprisonment – and yet you continue to love that artist’s work, in defiance, in secret, or in ignorant bliss. Let’s keep More often than not, this person – it could be a filmmaker, a writer, a painter, a musician – is a man, because more often than not, it’s talented men who talk about what they do in everyday life. How do I behave? And so, when it comes to assigning blame for these conflicts that rage inside of us—can I still see Woody Allen? Annie Hall Doesn’t sound dirty? Is it wrong that I feel a sense of pleasure when looking at the aggressive angles of Pablo Picasso Les Demoiselles d’Avignon?—The bottom line is that it is men’s fault. Why do they have to spoil everything?

And yet – with her exhilarating book Monster: A Fan’s Dilemma, To be published on April 25, essayist and critic Claire Deider holds up a small lantern in the dark. Is it ever possible to separate the art from the artist? And if not, is it possible to find a sweet spot between our anger and enthusiasm? These are some of the questions Dederer both raises and answers. Demon, However this is not so much a book of solutions as it is an examination of how to approach the art we love. Because the more deeply we engage with art, the more likely we are to be bothered by the sins of those who created it.

The list of people who have let us down, or worse, is long. Allen and Picasso, Miles Davis and Ernest Hemingway, Roman Polanski and Bill Cosby: As far as guys go, that list barely scratches the surface, yet Deidrer is clear that women are also a kind of force in creating their art. There may be demons, although their actions—as in the case of Sylvia Plath and Doris Lessing—usually include their identity as mothers. In other words, she doesn’t let anyone off the hook. (Wait until you get to the part about Laura Ingalls Wilder.) Yet somewhere between giving these troublesome geniuses a pass and tossing all their accomplishments in the proverbial drawer and tossing the keys away, Deidrer came up with a thought. Seeks, breathes the middle ground. She asks a lot of tough questions, especially about herself. For example, how can one see the cosby show After learning about the rape allegations against its star and producer? “I mean, obviously, it’s technically doable, but are we even watching the show?” She writes “Or are we witnessing a spectacle of innocence lost?” It’s the kind of question that, for a minute, makes you feel like you’re off to the races, but really you’re just at the mouth of an intricate garden maze, making it to the end without making too many mistakes. cannot be reached. turns.

Read more: There’s More To Say About Bill Cosby

For Deidre, the wrongs are the turning point – and perhaps the only path that can pass through anything to enlightenment. She delves deep into the idea of genius, both its glory and its limitations, and she begins with the tough stuff, opening the book with a anguished reflection on one of the most monstrous living artists most of us have ever met. Can easily name: Roman Polanski. In Hollywood in 1977, a French-Polish film director drugged and raped a 13-year-old girl named Samantha Gelly. He was arrested and charged, but fled the country and has since lived and worked in Europe, becoming a fugitive from the US criminal-justice system.

Polanski is also a filmmaker whose work Deiderr admires, and in 2014, when she was researching his output for a book project, she found herself confronting the troubling truth that although she fully aware of Polanski’s crime, but she was “still able to consume him.” Work. Eager to do.” As she sat down to watch her films in a room filled with books and paintings in her home in the Pacific Northwest—”a room that suggested—all those books—that human problems could be approached with careful thought and a sense of moral ethics. can be solved by application”—she felt strong enough to face her struggle, only to find that there was no easy way out: “I found I could solve Roman Polanski’s problem by thinking Can’t solve

The question of how we live with the art of “monstrous men,” as Deiderr calls them (when they are in fact men) is hardly going away, and it is rocky territory for anyone who cares about art. Presents. Because now, at least according to a new set of unwritten rules, we not only have the task of assessing the art at hand; We also have to make a judgment about whether its creator is worthy of our respect on moral grounds – and then submit to the judgment of someone else who finds our findings desirable.

Read more: Cancel culture isn’t real—at least not in the way people think

Here are some patterns. Do we judge a genius woman who abandons her children more harshly than a genius man who, say, emotionally and physically abuses the women in his life? Is the water wet? However, Dederer is arguing against easy morality, which is more for its own sake than for the benefit of humans at large. “The belief that we know better—a moral sense, if ever there was one—is too innocuous. This idea of the rigorous, gentle purpose of justice, liberalism, fairness is enticing. So deeply enticing that it distorts our thinking and our view of ourselves.” obfuscates awareness. We are the culmination of every good human thought.” In other words, even armed with our own ultra-pure judgment, we don’t always know best.

Deidre takes this argument to its necessary end. She’s tougher on herself than anyone else: a late chapter, in which she writes about her own alcoholism, and her own possible monstrosity, makes for stinging reading — if you’re going to point the finger at others. , she suggests, you have to be prepared to examine yourself as well.

Would it be too much to give away to explain how Deader finally solves the problem of monstrous creators? Or, at least, resolves it to the extent that any of us humans can? Demon Dazzling book. It’s also, sometimes, a maddening one. Deidre refuses to draw easy conclusions, always a plus. But in weighing the relative transgressions and merits, one says JK Rowling—whose views on trans identity have led to calls for boycotts even as her defenders say the fury is drowning out nuance—that Can also come across as hopelessly non-committal. At a certain point in the book, she balances two extremely complex figures on a delicately calibrated see-saw: on the one hand, the troubled poet Sylvia Plath, who took care of her two young children before killing herself in her London flat; prepared bread and milk for, and on the other hand, Valerie Solanas, radical-feminist author of scum manifesto and, perhaps more famously, the woman who shot and wounded Andy Warhol in 1968. Deider admits that it’s easier to empathize with the fragile, highly gifted Plath than the firebrand Solanas, even as she tries to elicit some compassion for the latter. You may come away, as I did, largely unaffected.

But again, anyone looking for easy answers has come to the wrong place. This is not a prescriptive book. It’s a bit awkward in places: Deidre tells us about the process she goes through to wrestle with these problems, but she knows she can’t solve them. For now, though, even the wrestling feels like moving forward. The genesis of this book was an investigation 2017 paris review Essay, “What do we do with the art of monstrous men?” Which seemed, if social media was any indication, to make a lot of people feel less alone, myself among them. Demon She’s more: it’s a secret look passed between friends, only in book form.

As a film critic, I side with Deidreer on Polanski’s genius as a filmmaker. (His most recent film, 2019 Ok, an astonishingly skillful account of the Dreyfus affair, was not released in the US) I have also had to contend with the sins of Bernardo Bertolucci (who was accused, by last tango in paris star Maria Schneider, was guilty of on-set misbehavior, and probably of the emotional kind, at least) and Bill Cosby (whose history of rape and assault allegations overshadowed his accomplishments as a prolific black performer in careers long overdue). has almost been eliminated. the cosby show, My own formula for separating the art from the artist is not at all: it is a more tragic calculation that acknowledges both the suffering of these people and the beauty of what they have given to the world. I would do the same for the women, if there were more female monsters. The best art reflects the human touch; The catch is that it also has to be made by humans, who are inherently messy.

If you, too, love the work of Polanski—or Picasso, Hemingway, Allen, Davis, and so on—then accompanying Deiderer on her winding journey may be the best gift you can give yourself. The final chapter feels its way towards a conclusion that burns clean, though it also hurts a bit. Our relationship to any work of art is open, Deider reminds us: “We change, and our relationship with that changes.” This is the nature of love. She quotes British philosopher Gillian Rose—”There is no democracy in any love affair: only mercy”—with her own observation: “Love is anarchy. Love is chaos. We are at the mercy of the art we make.” love, but its creator is also at our mercy. To forgive would be an easy thing; to love without it is very difficult.

Must read more from time to time

Contact at letters@time.com.