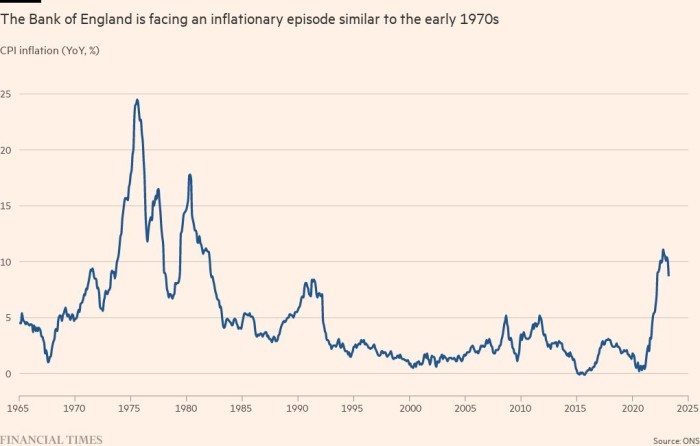

On the surface, UK inflation in 2023 is becoming akin to the 1970s, when everyone talked about the “British sickness” making the country Europe’s “sick man”.

Persistently high inflation that eclipses rates in other countries. Contracts, such as mobile phones, are linked to inflation, exerting price pressures. Officials struggling to control household spending. and wages after higher prices.

Certainly, UK inflation appears to be stable compared to other countries. This has been caused by a combination of strong spending at a time when labor markets are tight – also a problem for the US – and the residual effects of a steep rise in European bulk gas prices last year.

Stephen King, HSBC Senior Economic Adviser and author We need to talk about inflation, The situation was grim after new figures were released on Wednesday by the Office for National Statistics.

In April, the inflation rate was 8.7 percent, much higher than the 8.4 percent expected by the Bank of England.

“It’s not looking good, is it?” The king said. “Disappointing growth, not helped by Brexit. Real wages resistance. Core inflation highest in decades. BoE is admitting it has been using a model that hasn’t worked well of late. Policy rates now are also very low compared to the 6.8 percent core inflation. . . oh dear.”

The BoE has been caught for three months in a row for failing to understand short-term dynamics in prices. In February, the central bank had expected inflation to fall to 9.2 percent by March, but it remained at 10.1 percent.

When the BoE revised its forecasts this month, it built in new margins for error to improve accuracy. Privately, officials said the bank had done everything possible to ensure that the forecasts were not again too optimistic.

BoE Governor Andrew Bailey admitted on Tuesday that the bank had “huge lessons to learn” on controlling inflation and forecasting it.

He said the failure to recognize immediate price pressures in food was partly the result of adverse weather in Morocco, which had affected supply chains.

But he also acknowledged that the BoE did not realize that food manufacturers had locked out long-term wholesale contracts at food global commodity prices, which were near their peak last year.

Adding to the list of problems, it is clear that even the governor was not seeing the latest month’s 1.2 per cent rise in UK prices. Nor did they expect such a wide rise in prices, driven by increased prices for secondhand cars, large increases in the prices of mobile phones, as well as books, sporting and gardening equipment and pet products.

Even before the latest forecast errors, BoE officials were under pressure to explain to MPs at the House of Commons Treasury Committee on Tuesday.

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive graphic. This is probably due to being offline or JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

Although Bailey said the bank had already used its own judgment to advance its forecasts, he was criticized by committee chair Harriet Baldwin for only using models based on data that were relative to 30 years. Price shows stability.

BoE Chief Economist Huw Pill said the central bank is carefully studying historical data for insights on how best to control inflation. “we think [whether] We should be using models or revisiting frameworks applied to data from the 1970s and 1980s,” he said.

“But importantly, while there may be something to learn from this, there are also reasons to think that the experience is not immediately relevant,” Pill said.

Inflation was persistent in those decades, Pill said, because companies and workers expected inflation to remain high, and set prices and demanded wage increases accordingly.

Even though Bailey acknowledged that the wage-price spiral was driving inflation, his chief economist said that the current situation was different from the 1970s.

“The structure of the labor market is very different . . . and especially the system in which monetary policy is conducted is very different,” Pill said.

The BoE has insisted that most of the inflation came from a sharp rise in the prices of gas and food, which the UK imports and the central bank has no control over.

You are viewing a snapshot of an interactive graphic. This is probably due to being offline or JavaScript is disabled in your browser.

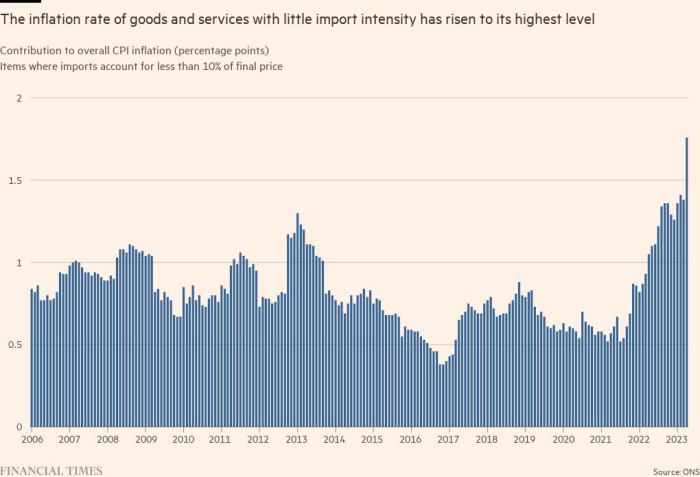

As economists pointed out on Wednesday, the problem with the BoE blaming inflation on imported energy and food prices is that it is becoming increasingly inconsistent with the data.

Core inflation rose from 6.2 percent in March to 6.8 percent in April when economists’ median expectations predicted it would remain stable.

Official data also showed that goods and services that contained some imported element were increasing the overall inflation rate faster.

In April, the ONS said items that had an import intensity of less than 10 percent, such as housing rent, contributed 1.76 percentage points to the 8.7 percent inflation rate. This was up from 1.38 percentage points in March and the highest level since the series was first published in 2006.

Alan Monks, UK economist at JP Morgan, said this was dangerous and would prompt the BoE to raise interest rates further.

recommended

,[The data] Monks said that cannot be described outright or simply as an indirect byproduct of food and energy price gains, as suggested by the BoE and Pigeons.

Echoes of the past spooked financial markets on Wednesday, sending hopes of future interest rate hikes sharply higher. Financial markets expect rates to rise to 5.3 percent by the end of the year.

That could exacerbate the problem, according to Sandra Horsfield, UK economist at Investec, who expects another quarter-point rise in June to 4.75 percent.

In a time of 1970s-style stagnation, with little growth and high inflation, she said: “A slight possibility cannot be ruled out, but it is doubtful that such a hard slam on the brakes is necessary.”